LISTEN NOW:

SUMMARY:

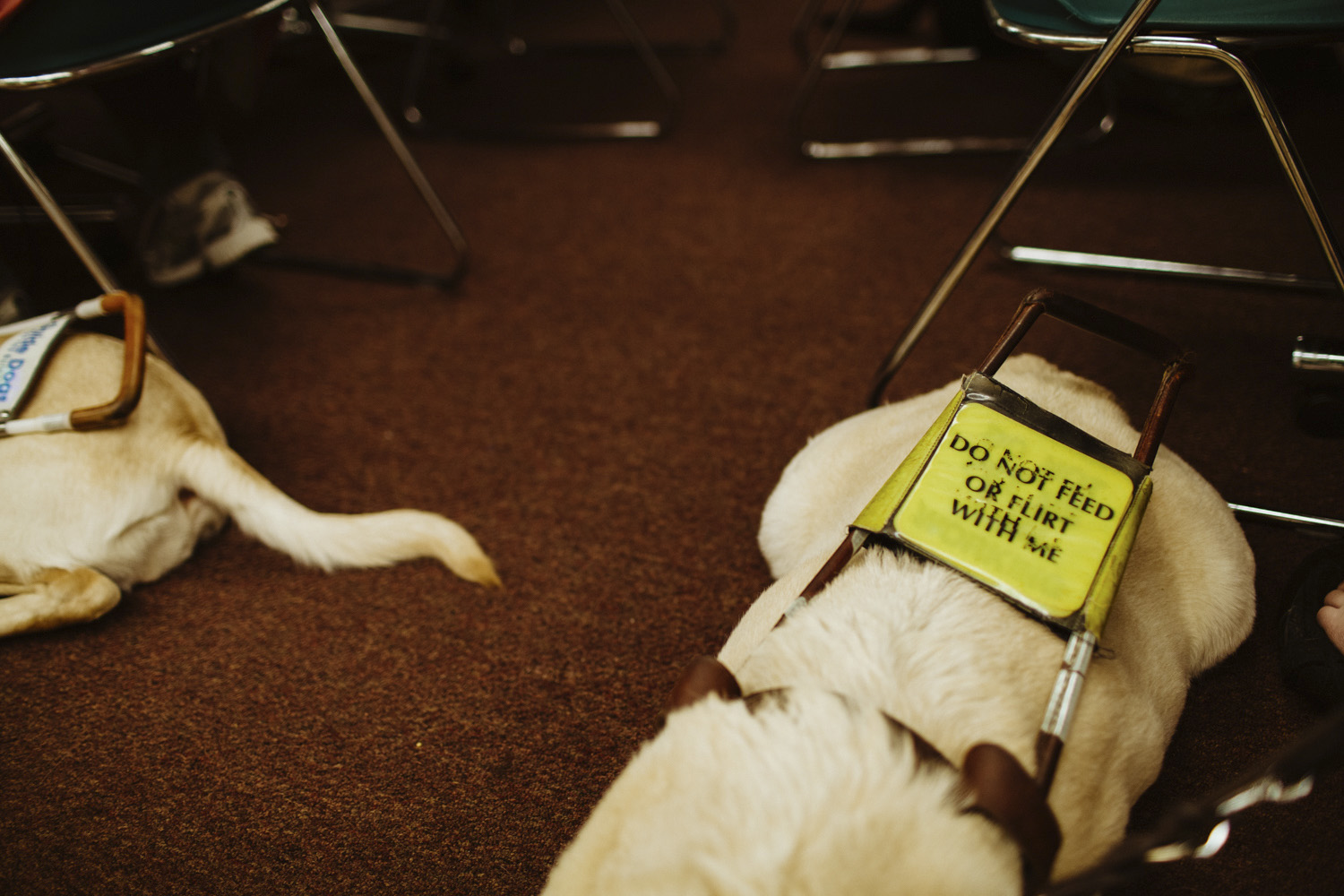

We join Clarence at Vision Loss Resources where he shares his story about working with guide dogs after losing the central vision in both of his eyes later in life.

Clarence passed away from a long battle with cancer after this interview. We’d like to dedicate this episode to his wife, Nancy, as well as all of his family and friends. Clarence had a passion for community involvement that allowed him to touch the lives of so many people from all walks of life. He will be deeply missed.

Music: Eric Matyas & Bensound

Photography: Natalie Champa Jennings

Additional Resources:

NOTES:

[4:20] Talks about his eyesight and difficulties

[6:50] Talks about his failure and his successes

[7:20] Speaks about guide dogs for first time and the process to get one

[9:15] Says that less than 1% of the blind choose to use a guide dog

[9:40] Talks about the safety that guides dogs allow you to feel

[10:15] Talks about his own guide dogs for first time

[11:00] Talks about how each dog has their own personalities, specifically his dog, Telly

[12:00] Speaks about his cancer for the first time

[14:00] Says that he owes it all to his parents and how their memories carry him through tough times

READ THE TRANSCRIPT:

“Nobody’d be able to tell that I was blind unless they saw me read. If I take off my glasses, or just wear contacts, I would blend in. Nobody would be able to discern that I was a blind, or legally blind person. My situation is: my left eye had a correction of 2100, and 2200 in the right eye. Correction means with glasses. I was a high—for all intents and purposes—a high partial. My wife’s eye condition is similar to what I once had. Although, I even saw more than she currently sees.

“In 1987, I had undergone a cataract surgery, which made it possible for me to read even enlarged screens two or three feet away, which was kind of nice. I didn’t have to have my face right up against the screen. Even with reading glasses I’d have to look really close, so reading has always been a struggle. The doctors told me that in about ten years I might be a candidate to develop glaucoma. My situation happened early. It happened prematurely and within five years, and nobody picked up on it until the fourth field test. By that time, the glaucoma had already set in. Then, the doctor decided to do laser surgery. He botched the laser surgery, and he hit the nerve. Within a week I lost the central vision in both eyes. From that point on, my vision—which prior to the laser surgery was stable—after the laser surgery, I began a long process of downhill loss of vision. Today I’m totally blind, and have undergone well over eleven surgeries, cutting surgeries, which were rather painful.

“In 2007, I had a retinal detachment and the doctor—and a good, very good doctor—discovered that I had a hole in the optic nerve. He was the first doctor, and the only doctor, who identified that. All we could think of was that that was the hole from the laser.

“We [people who are blind] are held to a different societal standard and one that is really unfair. Over scrutinized, a lot of mistreatment… I’ve been accused of lying, and why would I fake this? Or [told I] need to be more realistic on things I can do. Well, I think all of us have a realistic idea of what we can do by trying something. Sometimes we succeed, sometimes we fail. Failure is not exactly a bad thing. We learn a lot. I’ve learned a lot from failure. I’ve had a lot of failures in my life, but I’ve also had a lot of successes. I didn’t get to graduate school without hard work, and I didn’t get my degree, and I didn’t teach for about—I taught for 20 years—so having taught that length of time, evidently I was doing something right.

“The amount of testing the [guide] dogs undergo is rigorous, and it’s rigorous right up to the very end. If these dogs fail any one of those tests, they become a career change, meaning they won’t make it as a guide dog. You have a phone interview where you put in a request for a guide dog. If you’re going to be a new guide-dog handler, they accept you, and then they’ll do a second interview—a written one where they actually have a staff person come out and ask you a bunch of questions. Then they do a thing called a Juno, where they have an imitation dog (it’s just a rug that they hold at dog level) that they have you walk around with to get an idea of your cadence, walking ability, speed, pace, whatever. Then, the third time, they do another assessment, just to dot i’s and cross t’s, to make sure that by the time you go out there, they have a pretty good idea as to the dog they’re going to have for you. It’s a matter of making sure that they made the right selection.

“Today we are at a luncheon for Guide Dogs for the Blind. As you can hear, there are lots of people who are attending, all of whom have guide dogs. All of the dogs come from Guide Dogs for the Blind.

“People either choose to use a white cane, straight or collapsible, or a guide dog. Actually, those of us that use guide dogs, we’re about at, if not less than, one percent of the blind population, most of whom use a white cane. The preference is for ease of mobility, safety, and companionship. The dog and the handler develop an integral partnership where we function as one. It’s a safety factor. Some people feel safer using a cane, some of us feel safer using a guide dog. Safer in terms of crossing streets, pedestrian traffic. If a car’s crossing your path, the dog will get between the handler and the car to make sure the handler’s safe. I also use a cane at times when I walk the dog. There might be an area where I want to find out a little more detail that the dog can’t give me information about…then I use the cane.

“Cruiser is my third one [guide dog], and like I say, each one has a different personality. I’ve learned a lot about dogs since my first one, Frisco. I wasn’t partial to a lab until Frisco, and I would not have any other dog but a lab now. I think they’re extremely intelligent, very gentle, easy to work with, and all around good with people. Each one’s different. You have to unlearn the practice of the previous one and learn the practice of the new one.

“Cruiser is a lot more lively, a lot more willing to work, he loves work. Telly was a good guide but work was not his top priority. I’ll give you an example: When I retired Frisco, my first guide, and Telly was working, a cab pulled up—I had ordered a cab—and I leaned over and said it’s time to go. I put the harness on the dog, opened the door, walked out, I had the leash in my hand and I was holding onto the harness. We were midway down the sidewalk and I reached down, felt the collar: wrong dog. Frisco went into the harness! He went into Telly’s harness. Telly was still on the couch.

“That’s pretty indicative of how willing Telly was to work. He would prefer to stay home. Work was not his highest priority. Frisco was retired, he still wanted to work.

“A year ago, the furthest thing from my mind was that I’d have anything to do with cancer. It’s always been at the back of my mind. My dad died of cancer when he was forty-seven, so I always . . . I had that lingering thought that I might get it, but I wasn’t sure. My dad’s cancer may have been brought on by his wounds. He was severely wounded during World War II—shrapnel wounds. He died in 1962 at age forty-seven, so he was pretty young when he died. Last year, my oldest brother died of cancer . . . colon and liver cancer.

“I was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. I had six chemo [treatments]. I also had twenty-eight sessions of radiation. I’m now a cancer survivor in recovery. I will be visiting doctors pretty intensely for the next couple years. If the cancer does come back, more than likely it’ll come back within the first year or two. Five years out, I’ll be considered cured if I don’t have a relapse and I’m looking at the five year [mark] . . .

“Oh, I owe it to my parents. Like I say, my dad died when he was

forty-seven, and my mom died when she was sixty-four, but in the years when they were together, before he died—I was nine-years-old when my dad died—those were some of the most influential years of my life. Those first nine years of my life really set the tone for my life. The love, the care, the stability that they gave me carried me through some really tough times, years later. I look back on that and I’m very grateful for those times. We were a very close family prior to my dad’s death. I have very fond memories of Christmas, and family get-togethers. It’s a very warm, comforting feeling. I think back on that. That carries me through, like I say, has carried me through, and will carry me through, tough times, and what I may have in the future. I’ve got a good history to fall back on, and I owe it to my parents. They established in me, at a very early age, the determination to do the most I could with what I had.

“Do the most you can with what you have. Don’t let people tell you you can’t do something. Do what you decide you can do, the best way you can do it. •