LISTEN NOW:

SUMMARY:

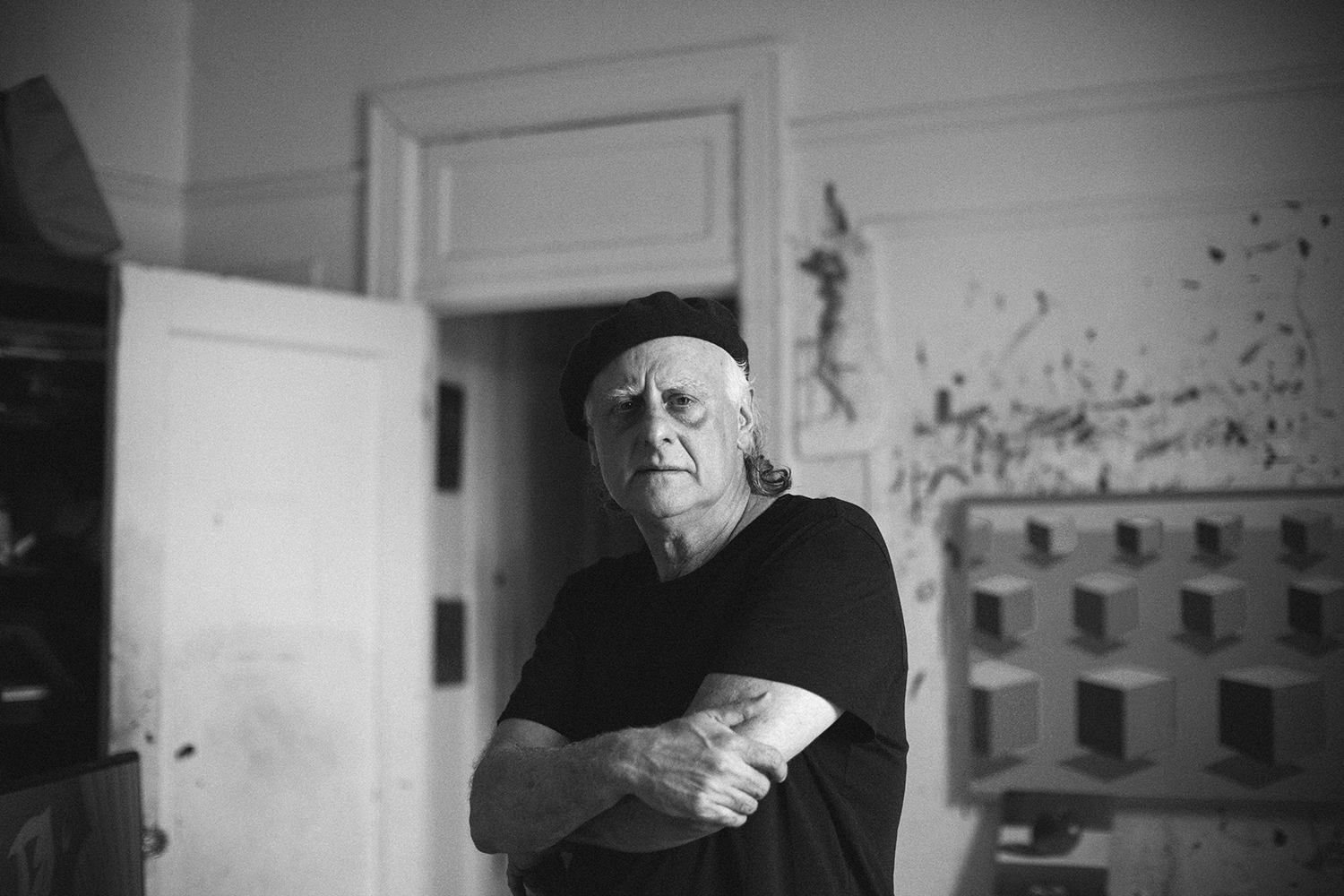

In this episode, Robert tells his story about life as a musician and an artist living in Brooklyn, NY. From co-founding The Shirts, touring with Peter Gabriel, and playing regular dates at NYC’s famed CBGB’s, to discovering his love of painting, this story is an artist’s journey.

Robert remembers his father’s cameo in On the Waterfront down on the Brooklyn docks. He talks about the little flukes in life and how one tiny thing can change the course of your life’s path dramatically and forever.

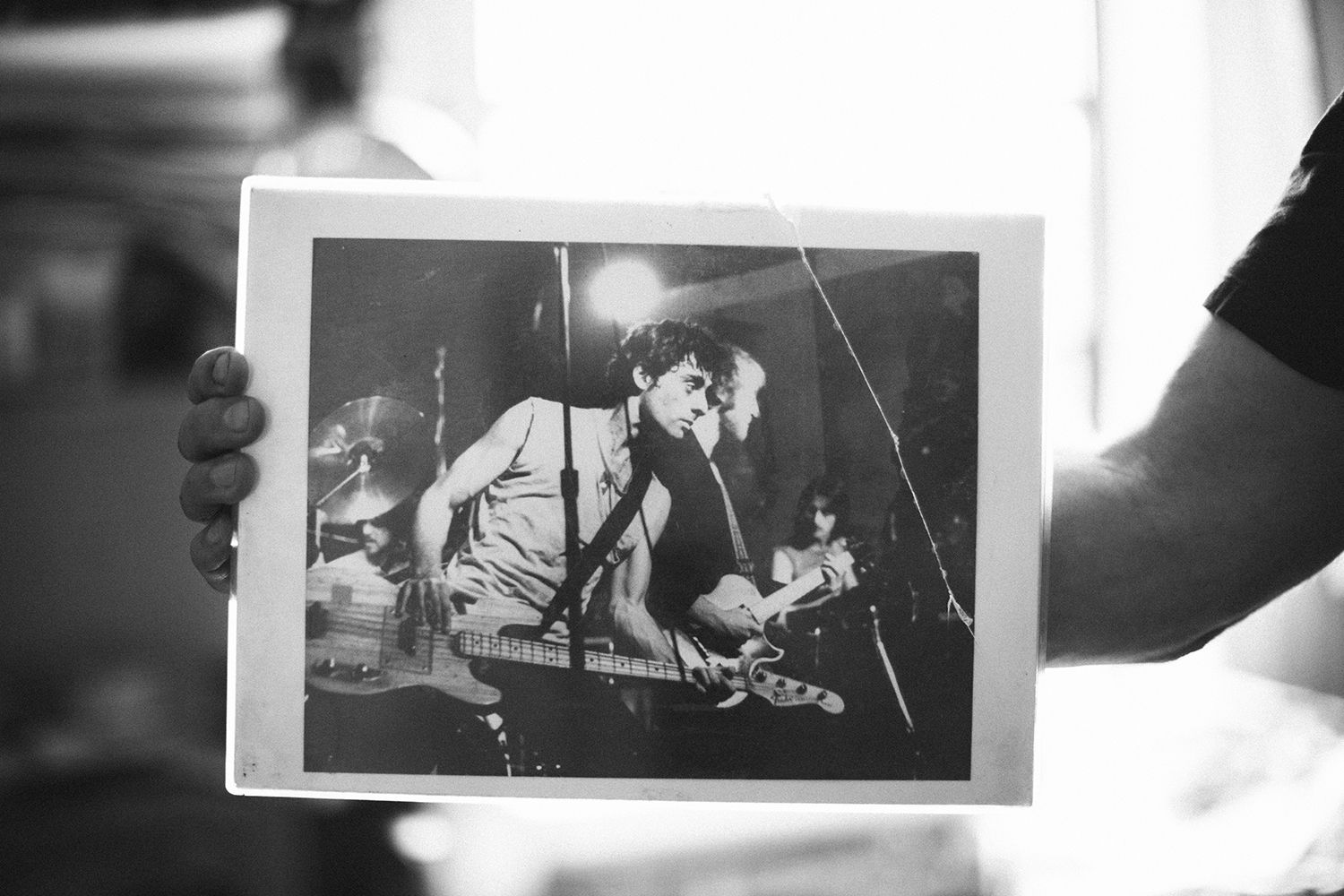

After missing the Vietnam draft by a hair, Robert helped found the New Wave group The Shirts under manager Hilly Kristal. After regular appearances at NYC’s CBGB’s playing with Television and The Talking Heads, The Shirts signed with EMI and toured with Peter Gabriel.

Later, after marriage and children, Robert discusses how painting and art saved him and how in many ways it was just by chance that he ended up where he is today.

Robert Box Twitter: @RBoxArt

RBoxArt@gmail.com

Music: The Shirts

Photography: Natalie Jennings

NOTES:

[10:00] Talks about how his grandfather came through Ellis Island

[10:40] Robert speaks about finding art in school

[13:10] Robert graduates high school and goes to the School of Visual Arts and drops out shortly after

[14:25] Talks about living in a storefront in NYC and starting his band, The Shirts

[15:25] Robert talks about the draft for the first time and how luck was on his side

[17:25] Talks about the opening of CBGB for the first time

[18:45] Speaks about being signed at the band’s lowest point

[21:15] The band opens for Peter Gabriel

[22:17] Robert talks about his advice: Just go, just work

[23:30] Talks about how that band wasn’t business smart and the ending of the band

[25:50] Robert talks about how he turned to tennis to get through while many of his band members turned to drugs

[28:00] Robert talks about his decision to set up outside of The Met and sell his art

[29:15] Robert says it’s all about people resonating with your art

[31:15] Robert talks about how people need art; like people need music

READ THE TRANSCRIPT:

“See, I feel like life is like a fluke. It’s real, things happen that just change. Little things, like when I went to high school, I had eight years of nuns. Then I went to a Catholic high school with brothers. Sophomore year I had this teacher, Brother Benild Montgomery. They would wear black robes. It was a homeroom class, about sixty boys, like fifteen-years-old. No teacher, everyone is screaming, yelling . . . it’s like a riot. This teacher walks in, this brother, and he screams so loud, “Shut up!” Everyone was shocked, everyone sat down. Somehow, I continued standing, I was amazed. He goes, “You?” I go, “Me?” He goes, “Yeah. What’s your name?” Bob Racioppo, Robert Racioppo. He goes, “Write me 250 words on Bertolt Brecht. Have it tomorrow, as a punishment.” I didn’t do it. The next day he goes, “Well now it’s 500.” It kept going on until he said, “Well now it’s 2500 words on Bertolt Brecht.” I said, “Oh I better do it.” I got a book on Bertolt Brecht out of the library, and I started copying it and reading it.

“Suddenly, I said, “What is this Bertolt Brecht stuff?” Then I got to The Threepenny Opera that he wrote. He wrote “Mack the Knife”. “Mack the Knife”—you know it by Bobby Darin—but in The Threepenny Opera it’s like, (sings) “Oh the shark has . . . ” That brother got me into art. I started writing poetry, and suddenly I said, “Wow this is great.” I got into art, and poetry. That’s what got me into art.

That changed my whole life, yes. That whole thing.”

“Okay, I’m from Brooklyn. Right now, I’m living in Park Slope, which is a little uppity compared to where I grew up in Sunset Park, which was down near the docks. It was a real working-class area. My father was a longshoreman. We were just real working class. Brooklyn was a lot of working-class people, and a real mix of Italian, German, Irish . . . that sort of thing. The movie, On The Waterfront, my father was actually in it. They were filming where he was working. There’s this one scene anytime I watch, and there’s this really good shot of him, and he’s just, you know . . . (trails off)

“My father’s father came through Ellis Island in 1899. Someone saw his paper from Ellis Island, and his name was Rafaelo Racioppo, and the occupation said: peasant. He was an actual peasant. That’s America. My grandfather’s a peasant, my father’s a longshoreman, and I’m, in quotes, an artist. That’s America. I don’t think that happens other places . . . imagine being an actual peasant. That’s like weird, it’s like [being]- a serf.

“The funny thing is, it was a very working-class area, and the only thing we had was sports—fighting, and stuff like that. Art really didn’t exist in my clique. I joined the art program. You could become an art major in high school, so I became an art major. The teacher was brother Jonathan Ringkamp, who was an artist in his own way. He had won a Fulbright. He was really a pretty good artist on his own. Now there’s twenty boys in this class. The brothers were very rough, they were allowed to smack you around. It was like a thing, but usually they would surprise you and smack you. He gave us an assignment over the weekend, paint something . . . whatever it was. Monday morning, turned out not one student in the class did the assignment. Not one. Smoke was coming out of his ears.

“He goes, “Okay nobody did it? Get on line and give me your excuse why you didn’t do it. If I don’t like your excuse, I’m going to smack you across the face.” Now, we get on line. We’re standing in the line, this guy goes, “My dog ate it.” Bam. “I had to help my mother.” Bam. I’m sitting here, I’m sweating, what am I going to say? I have no excuse. He got to me, and I go, “Brother Jonathan, I have no excuse, I just didn’t do it.” He pulls his arm back and stops right at my face, and he goes, “You told the truth, sit down.” He didn’t hit me. After that, I became great friends with this guy, and I really learned a ton of art from this guy. It’s such a strange story. You couldn’t do that nowadays, but that was part of it. It dated back to the eighteenth century—spare the rod, whatever. It’s an all-boys high school, so it’s crazy anyway.

“I was on the tennis team. You couldn’t have long hair, but the sports guy, Mr. Nast the gym teacher, he said, “You got to cut your hair.” You had to have shorter hair than the rest of the school. I said, “No, I’m good with the school.” He said, “No, no I make my own rules.” I protested, but I quit the tennis team. Whatever. That was the end of my athletic career. I did art, and then I graduated, and went to the School of Visual Arts. The first year was great, and the second year . . . It’s hard to imagine, I talk to people your age about the sixties, Vietnam, and the war . . . the world’s sort of crazy now, with Donald Trump, but it was really crazy then. Oh, and Kent State happened where four kids were killed. Everything went nuts, and it was just constant demonstrations. School went on strike for a month. And then I just dropped out.

“Then I had moved out of my house. I lived in a storefront. After I left home, I wasn’t in much contact with my parents. When I quit school, I moved to this storefront and started this band, The Shirts, with my friends. Sunset Park, everyone wants to drink and get high, whatever. It’s not the suburbs. We didn’t have basements, or anything. Kids would get together and rent a storefront for a hundred dollars, just to party in, right? But you could live there, so I said, “I’ll live here.” I slept on a couch, and my rent was ten dollars a month.”

“I would drive a cab two or three days a month, and just write music, and work on music. I was painting, also, then. It was this crazy, bohemian existence. Also, when you go to college you get a deferment, so when I dropped out, I lost my deferment. I got a letter that I had to go to my draft board. The funny thing was, my draft board was in Coney Island. I had to take the train out to Coney Island. I went into this building—it was a movie theater with offices on top—and I walked in, and there was no one there. It was completely deserted, I can’t explain it. It was so run down. I walk through all these corridors, and this guy is sitting there, and I give him my name. He says, “Okay you’re 1A.” He hands me a card. I say, “Okay.” I went home. I sort of hid it when everything was starting to end.

“Eventually I went home, and I had gotten all of this mail. I had gotten these letters that I had been drafted, but I didn’t even know. I said, “Well I don’t know, I’m just here.” Then the war ended, and they never . . . I said, “Well I guess I’ll just go when they come and get me.” I said, “They’re going to come and get me.” They never came and got me. I don’t know, they forgot about me. The war had wound down, and everything ended. It was just like a fluke. I just lucked out. I’m not going to Vietnam. I would have went, because I wasn’t a conscientious objector, but I wasn’t gung-ho. I said, “If they come and get me, I’ll go.” I just would have went. Somehow I got through that, just by luck.

“A few kids actually came back, they just came as junkies. A lot of guys came back with real drug problems. They never got better. That was the real horror. I know, of course . . . dying. Now we’re friends with Vietnam, and all these people, I don’t know. That’s like over my head, to think of politics and war.

“After five years of being in the storefront, basically, this club CBGB opens. They only wanted originals. Our first gig we played with Television. Our second gig we played with the Talking Heads, and everyone was nobody. We were influenced by the Beatles, the Stones. We had a sound, sort of pop rock. We had a female singer, Annie Golden, who’s sort of famous now. She’s in Orange Is The New Black. Her name is Annie Golden—she went on to be an actress. They called us pop-New Wave. New Wave was the term for pop . . . sort of like Blondie. Something like that. We just kept playing. We got a manager, we played CBGBs, and record people were coming down. You could go in there, and you’d actually be sitting next to David Bowie. People just came there. It was like this magical place. Almost all the bands got signed. Then eventually, we had a manager. This guy Hilly Kristal—actually was the owner of CBGB—was our manager. Capitol passed on us. One night, this guy from EMI was there, Nick Mobs . . . the guy who signed the Sex Pistols happened to be in CBGBs. We were playing.

“This is really amazing. Then, we lived in a house, and we just refused to take jobs. We just couldn’t work. Hilly gave us a moving truck, we used to do moving jobs. We rented a brownstone in Brooklyn, and we couldn’t pay the rent. They turned the electric off. It was basically over, it was really weird. We were sitting in the kitchen one night with candles, and it’s the winter now. We were so destroyed, but we didn’t care when we had no heat. The landlord turned off the heat, everything. As long as we had electric . . . but then they turned off the electric, so we couldn’t even practice anymore. We couldn’t even play. We were sitting there drinking beer, with candles, and we’re in the kitchen, and one night, we made a big fire on the table. It was like, fuck it, we’re so doomed. We doused the fire, and we all just went into our rooms. The next morning, our manager got a telegram from EMI saying, “Caught The Shirts at CBGB’s last night. Must sign them. I’ll be in touch.”

“At the lowest point . . . It’s like a Cinderella story. The next morning, after that night, our manager called us and said you guys got a deal. We signed a deal with EMI. A month later, we’re on a plane to England to record our first record. We’re on a balcony. This is a balcony on top of Court Road in London. We spent like three months in London recording a record, and there was a whirlwind of five great years. Our thing was: get a record deal and then that’s it. We didn’t realize that the work started then.

“Our main tour, we did about twenty-five dates opening for Peter Gabriel, when he was doing that Strawberry Hill tour. We played arenas opening for him. We played in Bristol, and Peter Gabriel was looking for an opening act. He was looking for the right type of music, and we were sort of artsy, rocky. He came to see us, and he really liked us, so he put us on tour with him. It’s these kids from Brooklyn, The Shirts. We were crazy, because all our friends worked for the gas company. Where we lived, some kids went to college, but either you went to the gas company, or bus driving, stuff like that—working class stuff. We said, “We’re going to be rock stars,” and our parents told us we were crazy. Even our friends told us we were crazy. Our close friends . . . because everyone else worked jobs and we were living in the storefront, just living a crazy life.

“We had a thing of, “Just go.” We’d have a gig in some obscure Jersey town, and we had a big truck with all our equipment—this was before we got signed but we had a manager—and we’d get lost, and we’d say, “Just go.” We just kept driving, and somehow we’d get there. The main thing is, I say, just work. Go, just go. Just do it. Everything should fall into place. It might not, but if you just concentrate on your work . . . T.S. Elliot has a line, “Take not thought of the harvest, But only of proper sowing.” Do you job, you know how to do that.

“We weren’t that smart about business. I won’t tell you we weren’t smart, but we just didn’t even want to deal with it. If we had a great, incredible manager, it would have been good. Our manager was nutty too. We had five great years. We did three albums on Capitol, and we always used to go up there, they were friendly. After our third record, the way the corporate world works—which we didn’t know—all of sudden they wouldn’t take our phone calls . . . what happened? They didn’t pick up the fourth option. They don’t tell you, they don’t say, “We’re not picking it up.”

“The wall goes up. I compared it to . . . there’s a novel by Franz Kafka called The Castle. Did you ever read it? It’s like this guy, he goes, I got to get into the castle, and his whole thing is trying to get into this castle, but it’s impossible. He keeps going along, he’s meeting all these [people] . . . it’s sort of like that. There’s a wall that goes back up. I don’t know how, somehow we broke through it originally. Once the wall goes back up . . . that life sort of really, really ended.

“I didn’t know how to balance a checkbook, because our managers, they paid our rents, they paid everything. We were like children. It was sort of depressing. As luck would have it, some of the guys in the band started drinking heavily, doing drugs heavily, because it’s depressing. You’re on this other world, and now you’re back in normal life. Which is okay, but it’s different. I was driving a cab again. My girlfriend at the time dropped me, everything just went. Now, I don’t even have the band, because then we were like a gang. By luck, I got an apartment in this building, and I was sitting here very depressed. Again, I had no electric . . . somehow something went wrong with the electric. For the first month I lived here, I didn’t have any electric. I was sitting here. But luckily, across the street are tennis courts. I started playing tennis again. I didn’t get into drinking, I became obsessed with tennis. That got me through when I was driving cabs. Then I met Jane, so a lot of good things. Jane helped me a lot. We just worked out.

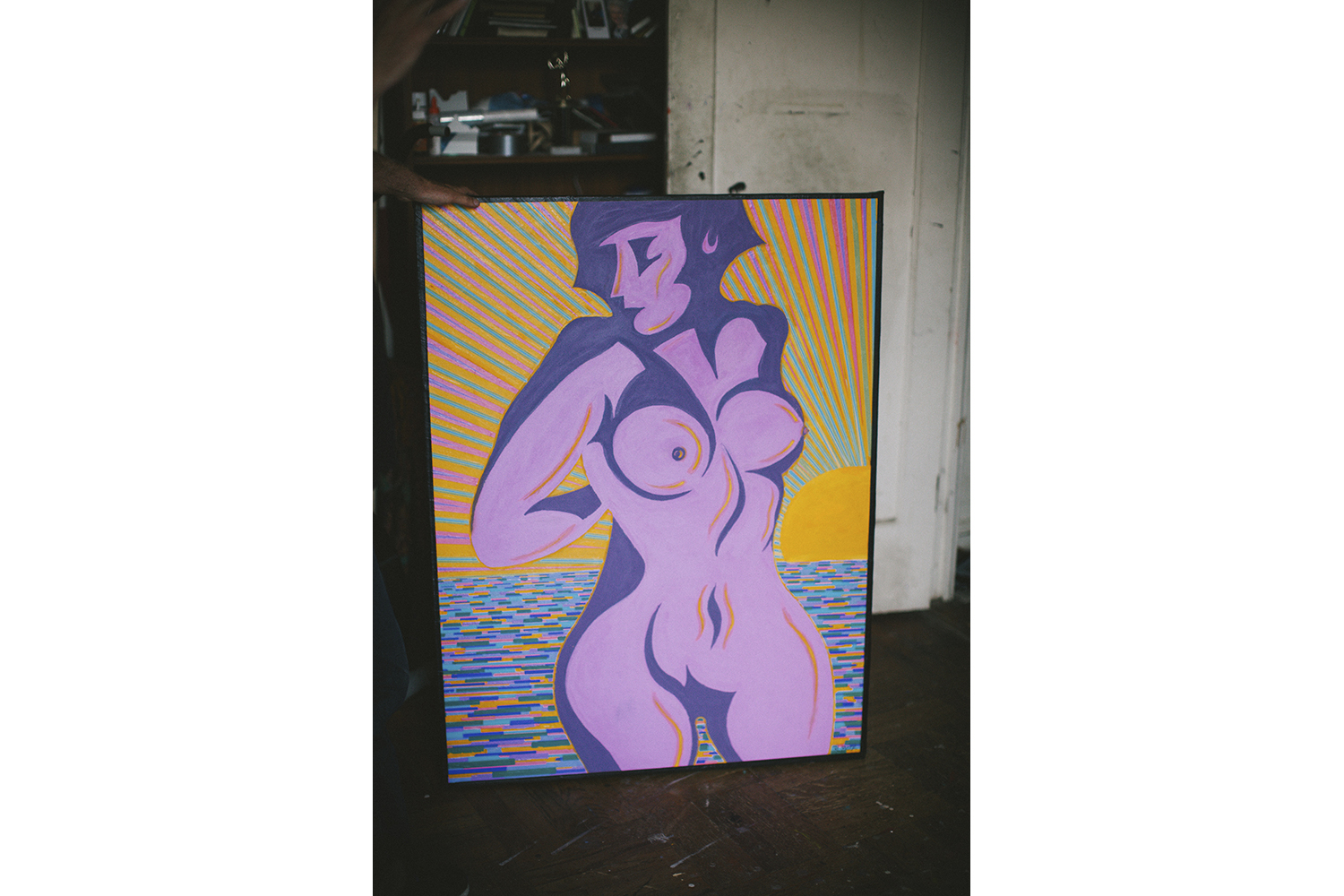

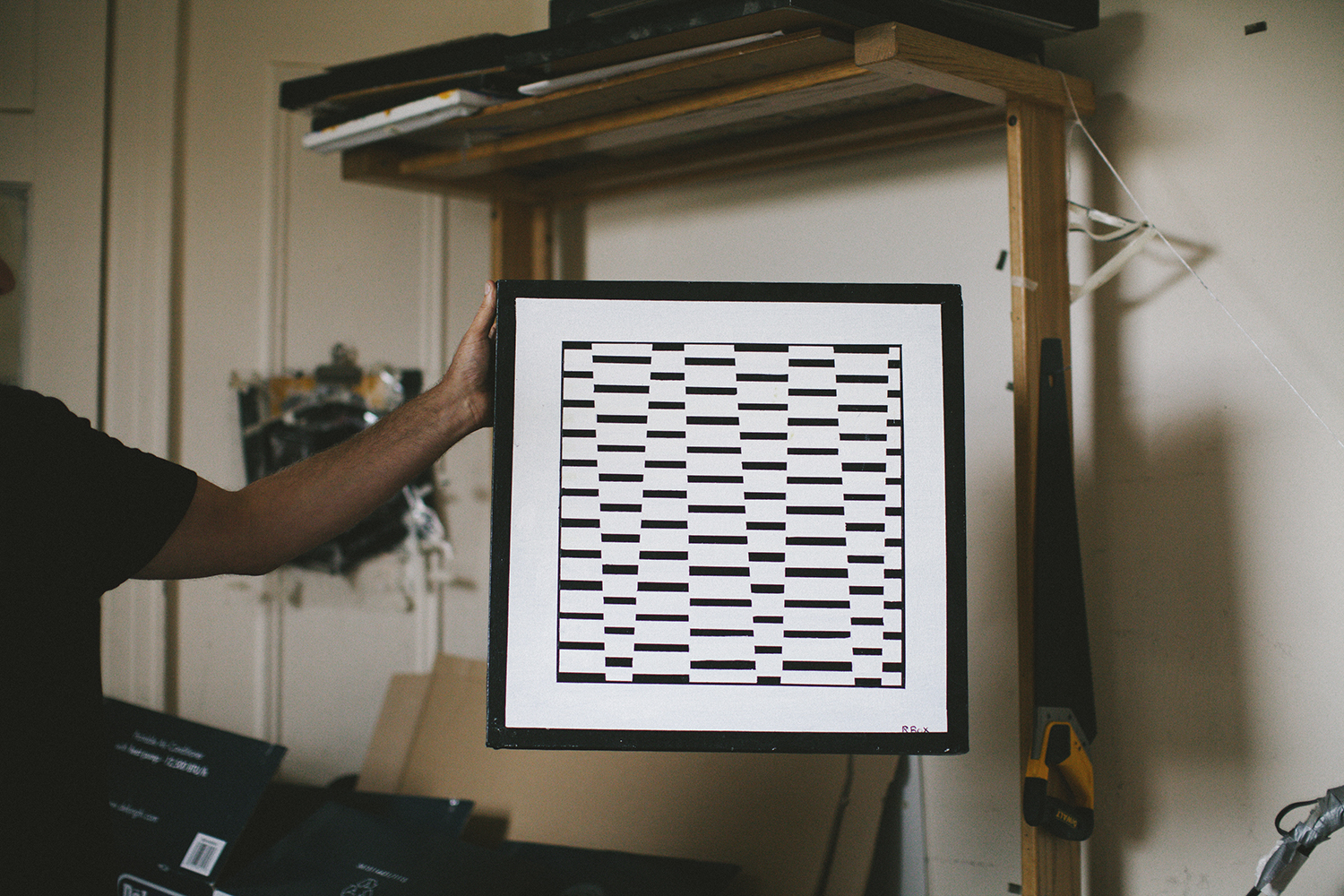

“You live various lives. That life sort of really ended. I still play a little music. Then I switched back, I fell back to painting. Art really saved me, it’s what I like to do. The rock-and-roll lifestyle . . . you don’t go to bed until four or five in the morning, because you work until two in the morning at a club. Even though rock-and-roll ended, I always painted at night under fluorescent lights. Then when I met Jane, we got married, we started having kids, and my only free time was six a.m. to eight a.m., because once the kids woke up I couldn’t paint. I started painting in the kitchen when I had that free time. It’s a confluence of strange things that led me to this style, led me to actually selling paintings. The morning sun comes in, there’s no buildings, so the sun comes up, and it seems at seven a.m., anything I put on my kitchen table—I could put an apple there, anything—the natural sunlight hits it, creates a shadow and a shine, it’s just very simple and nice.

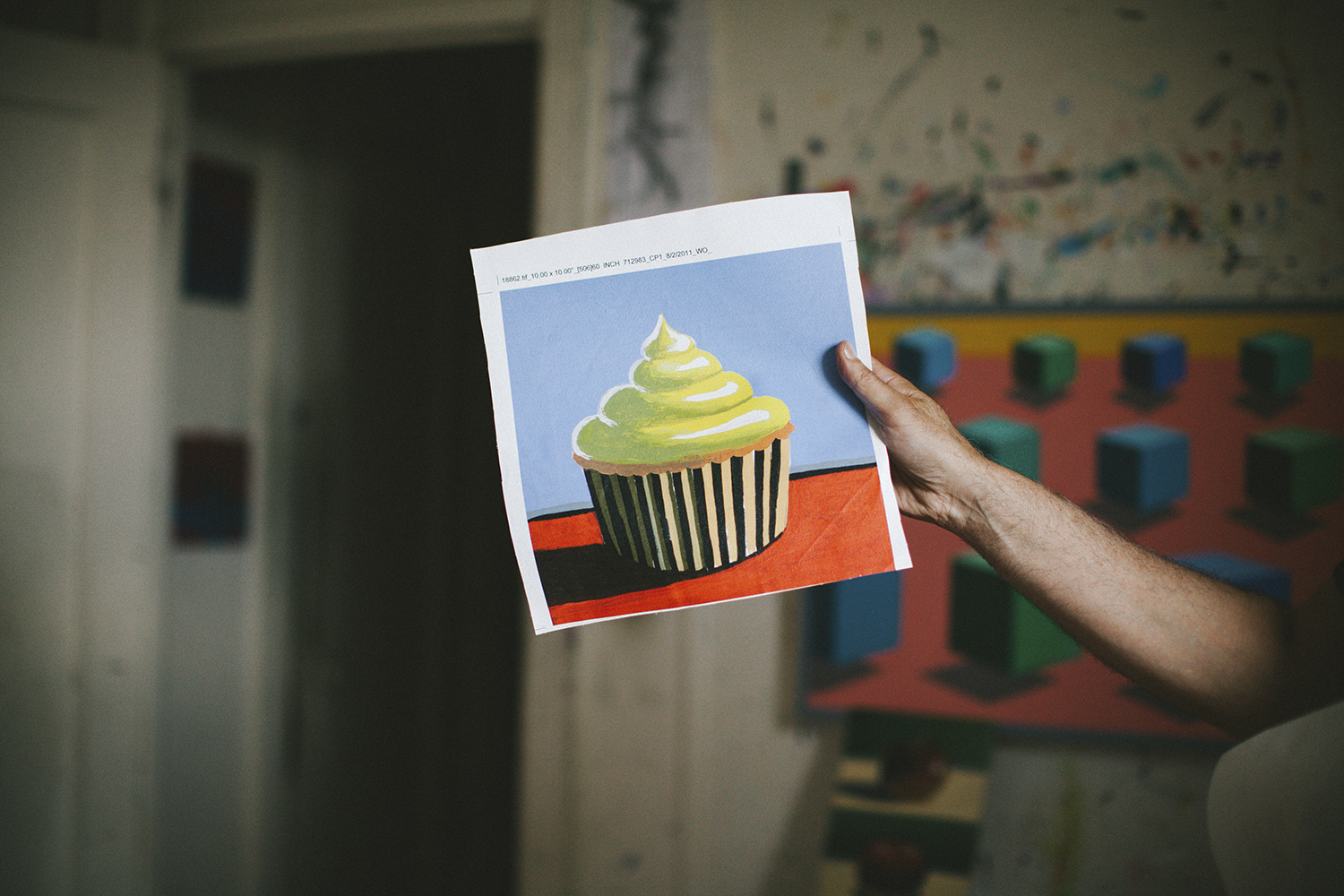

“I have a certain style. I used to be an abstract painter for many years, I never sold. One day I painted a coffee mug, I don’t know why, I just painted a coffee mug and people said, “Oh, if you paint coffee mugs, we’ll give you money.” I started painting coffee mugs, coffee pots. The show I had in January, I did a wall with thirty little squares, all different colors. It was great. Actually, I went to the show at the Met—I think it was the Vermeer show, it was great—and I walked outside, and I never noticed all these artists selling stuff. A lot of it is just like prints and stuff, New Yorker stuff, but there were a few artists. I said, you know, let me come out here.

“I was doing this kitchen stuff, and I remember my first sale. I set up right by the Met, and I just put some stuff on the ground, a cup or whatever. I remember these two Swedish stewardesses, they were sort of tall, blonde, they go, “Oh, what’s this?” I say, “It’s just art.” Oh, we like this, how much is this? I say, “Oh, twenty-five dollars each, twenty. They gave me forty-five dollars, and took two of the paintings. I said, “That’s it!” I went home and I said, “I got to do this better.” Then I got a table. It was amazing. The people you meet outside. There’s very few artists there, because it’s very hard. You get so much rejection.

“Let’s say last weekend—maybe a thousand people walked by, maybe two thousand, five people bought. I’m getting like 2,000 rejections, but five accepts, with money. A lot of people say, oh it’s great, but when people give money, then you really know you resonated with them. That’s the thing, that’s what I was about: artists who resonate. To do something that someone else can see, and they start vibrating, they pick up on it, because a lot of times you do art, and it’s not resonating. To me, art is you look at it, and it strikes you, or it doesn’t. It’s not a verbal thing, it’s a visual thing. There was this thing The Gates [in Central Park] . . . They did this project of orange flags. It was this big thing—it was a huge abstract thing that they did, orange flags all through Central Park. And it was a big thing, people walking through all these flags. When people came out of that, I sold out that day. That was the one day that I sold every painting, because people were so infused with art.

“I have to go through a lot of rejection. If you don’t get lucky early, you’ll probably give it up. Art is weird, it can give you a lot. What does it give you? You forget about life and death. When you’re really in the middle of it, you’re not aware of yourself; you’re not self-conscious. The ego, whatever that is, seems to float away and then you wake up and go, “Oh yeah.” Then your ego’s back, and says, “Oh yeah, this art is good, blah blah blah.” In the experience of doing it, creating something new, I always worried, “Well what if people just stop buying art because they don’t need it?” Then I was walking along one night, I had gotten a beer and I was just walking down, and if you look into any apartments that you can see—not that I’m a Peeping Tom—you can see walls, and every wall has a piece of art on it. People do need it, just the way they do need music. Look at me. I stand on a corner, so what the hell do I know?

“You see art schools and everything . . . .one of the reasons I dropped out of art school—this is another interesting story—freshman year I had real good marks, and I was doing really good. Sophomore year, I was actually doing some film. We had this film class with this guy, Leo Seltzer, older guy now. He said, “Okay, everyone is given a role of 16 millimeter film, shoot whatever you want, whatever you think is good, and bring it back and we’ll review it on Monday.” About twenty kids, young boys and women, and whatever. We started screening them, anonymously. People would screen it, and he would show it, and criticize it, blah, blah, blah . . . criticisms were good and bad. And now he puts on my film.

“I went into the subway and did a series of double exposures. If you go to 34th Street, there are escalators on the 34th Street train station, and I did double exposures—black and white—of people going up and down. After a while, it was double and triple, all these people going through each other. It was just a roll of black-and-white, 16 millimeter. Now, I’m sitting there, and my film shows. My film. It ends and Leo Seltzer . . . the guy gets up and goes, “Okay, now this is an example of pure idiocy.” No one knows it’s me, but I know it’s me. Now, I’m nineteen. As an artist, you’re still . . . okay, that’s Part One of this story. Then, I was like, “Oh fuck.” It really destroyed me.

“Later that day, there was a little screening room. They had screening rooms, where I was on a little projector, and I was screening my film. This guy walks in, the head of the film school. I’m looking at this thing on a little monitor. He comes over my shoulder, and he starts watching for a while and he goes, “Oh, wow. Who did this? Whose film is this?” I go, “I did it.” He goes, “This is absolute genius.” At that point, my mind went boosh. Art is so subjective. You have to define, you have to be really strong. That’s part of why I dropped out of school, because I was like, if one guy says it’s horrible, and one guys says it’s genius, it means they don’t know anything . . . I don’t know . . . who knows anything?” •