LISTEN NOW:

SUMMARY:

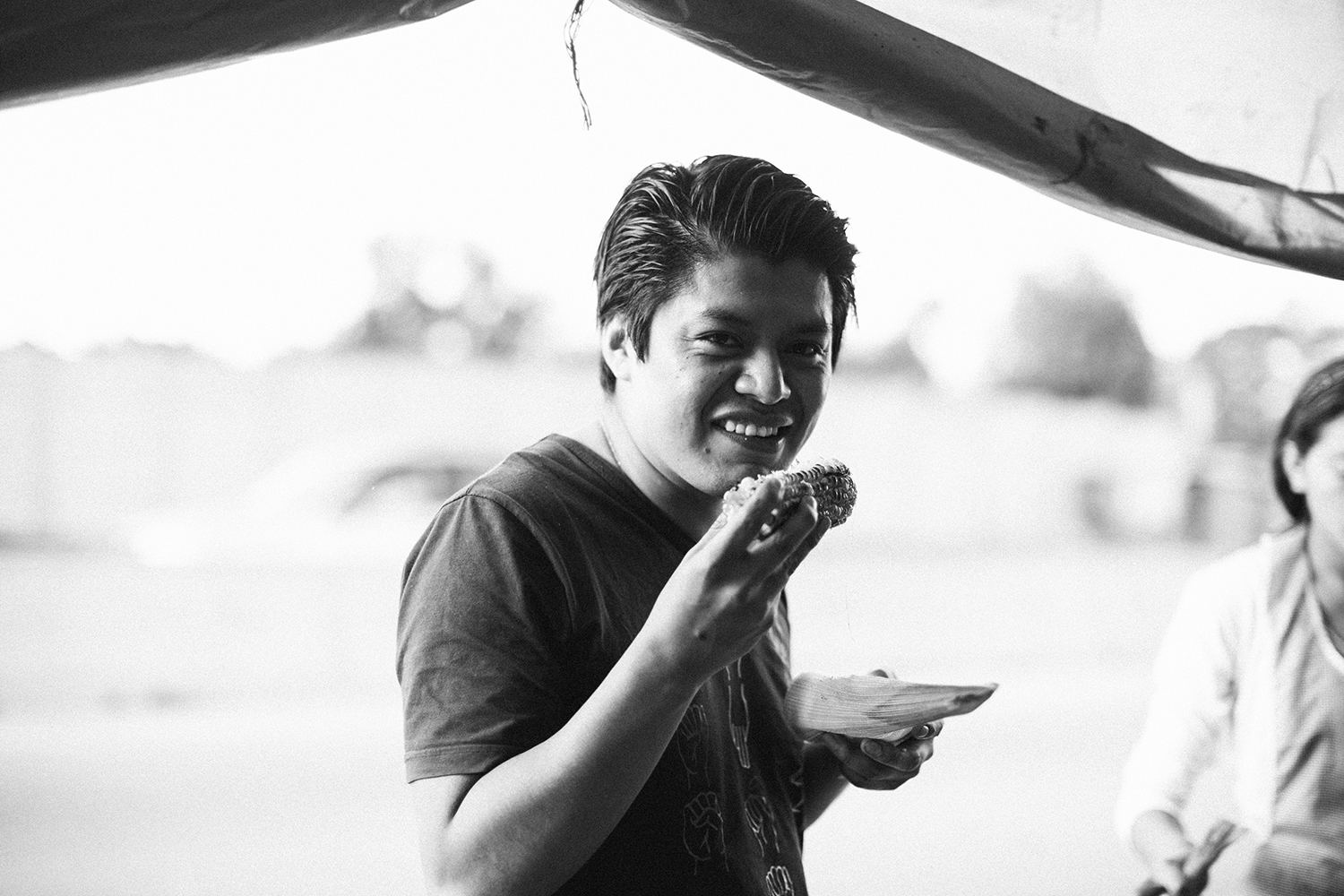

AFP takes the podcast to a remote Mayan village in Guatemala where we hear from Alejandro. Alejandro shares his story about growing up in rural Guatemala and his take on culture, language, and how important it is as a global citizen to experience other places around the globe first-hand.

Music by: Mato Wayuhi

Song: “Where Do We Go Now?”

NOTES:

[01:25] Natalie talks about being on the road the last couple of months & the mic set-up

[05:20] On speaking his native Mayan language–with a sample phrase

[06:30] The decision to go to a better school as a child for a better life

[07:50] Learned most of his English from living with Americans who changed his life

[09:40] Basic needs vs. luxury/United States vs. life in Guatemala

[11:00] Patzun and life

[12:00] Culture of undermining the Mayan people

[13:40] On valuing his language and culture

[14:30] On speaking his native language in public

[15:10] On forgetting language & culture

[15:45] The benefit of speaking Mayan/Kakchiquel

[16:15] Be proud of your heritage

[16:45] His wish to see more proud Mayan people

[17:20] On practicing non-judgement

[18:12] Do the fieldwork, get out and see the world

[21:14] “Where Do We Go Now?” by Mato Wayuhi

TWEETABLES:

READ THE TRANSCRIPT:

The times that I’ve spoken my language in different ways, especially when I went to the states, I got the comment that, “Is that German? Is that German?” I’m like, “Nope, it sounds just as good, but it’s not German.” It’s Kakchiquel. The language is Kakchiquel. It’s from the K’iche’ family.

Kakchiquel. That means, “When you are in sadness, when you have difficulties and problems remember that there’s always a friend who’s going to help you.”

Alejandro sounds more fancy down here, but it’s more difficult for Americans to say it. In the states, Harrison, it’s easier and people remember that, so I play with that. Harry Harrison Alejandro and I am from Patzun, Chimaltenango.

Just like a regular Guatemalan family, my parents had to decide where I should of gone to school, and that was in 1998. Back then they couldn’t pay for school. My dad, my biological dad, here in Guatemala, he decided to be a pastor. Pastors here, they don’t have a wage, they just get whatever the church can provide them, which at the time it’s not big, it’s not much. I was living in, not in really good conditions as far as housing, food. We were four brothers and two sisters, to make up a family of eight. We knew that a private school was better, better education. I didn’t know that I was going to learn English then. I just thought I was going to get a better education.

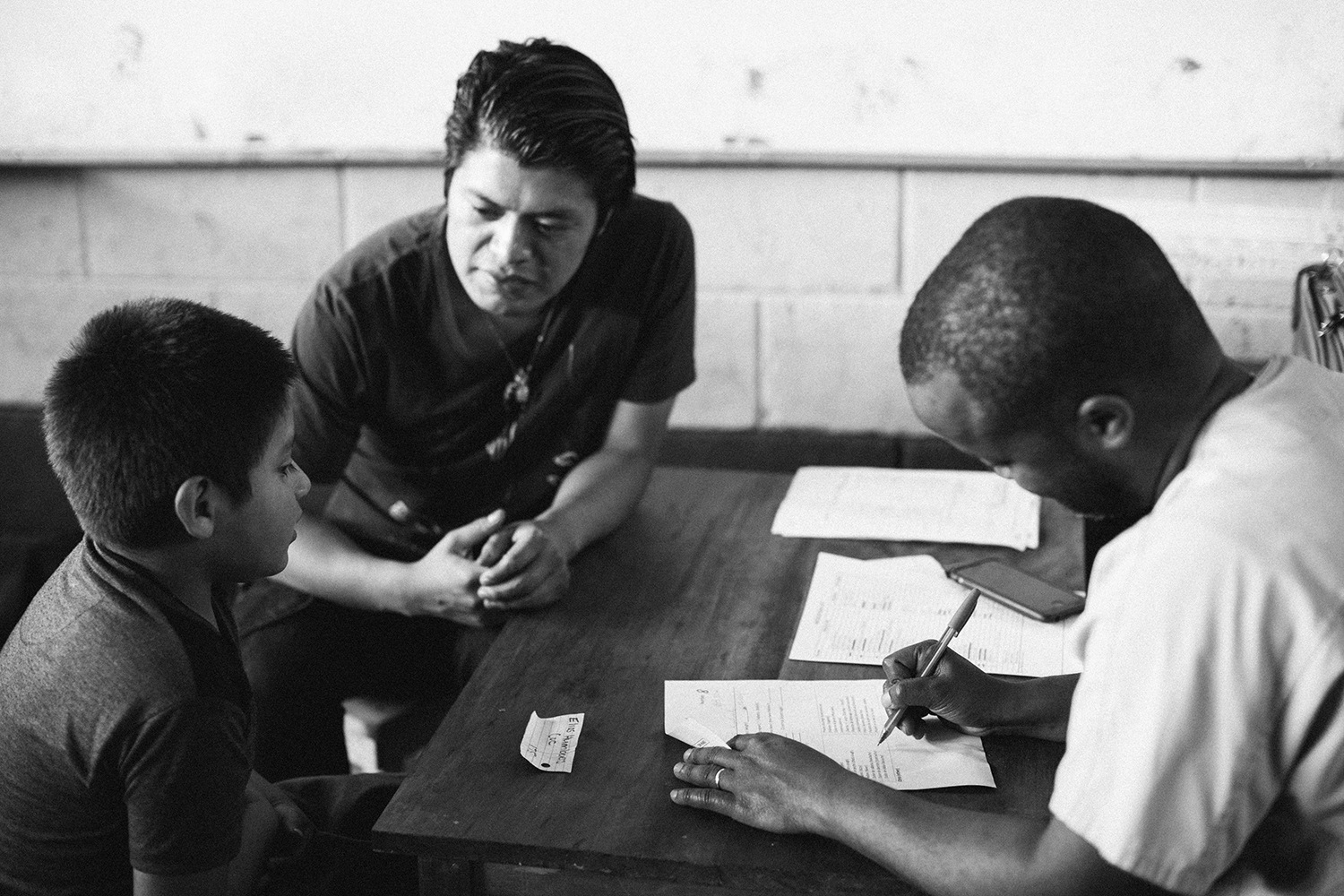

We said, “Well let’s go to…” which is closer, in Antigua. That’s where I got my four and fifth grade. Then I got my seventh, eighth, and ninth. During this time that’s when I met an American family in this orphanage, and that’s where I learned most of my English, because I lived with Americans. We just became friends. It was like a mother son relationship, during this time without us knowing that it was actually that way. They started paying, at some point, my education. Then I was able to go back to my original family, back into Patzun, with their support.

I decided that I wanted to go to college, and they kept supporting me in college. I went here to the National University. We tried, in the beginning, to get me a Visa so that I could go to the states and visit, and browse colleges and see what options, but that didn’t work out. I was denied the Visa, twice. I actually applied at UAH, University of Alabama in Huntsville, and I got accepted. I did all the documentation, by then I had gone to college two years already. I did the paperwork to transfer those credits to UAH, and then I just graduated in three years and a half.

Then I came back to Guatemala in 2012 just because I wanted to get back here. I miss everything about Guatemala. The landscape, overall, up there in Alabama all you see is just flat. I can see big differences now, because I’ve been in two sides of the world. I know that there are parts in Guatemala that in which they live like North Americans. What is a basic need, something that is really basic in the US, it’s a luxury in Guatemala. For example, you get tap water all day long in the states, but in Guatemala you get one hour of water a day, if you’re lucky. Sometimes you just water three times a week. Sewage system, there are places here in which you still find big holes, just people dig down the hole, make a toilet out of it. For us to have toilets and great sewage system that would be a luxury for us. I’m speaking for most of the population. I’m not speaking for 100% of the population, because I’d be lying, but that’s what the average Guatemalan does.

My town is Patzun. It’s one city in the state of Chimaltenango, and Guatemala’s got 22 states. 90% of the people there they’re from Mayan descent, so people there they don’t, well mainly woman, they don’t use western-style clothing. They have their traditional Huipel top, Corte at the bottom part. The man, the elderly man, they use their typical men outfit, but men are getting more and more of the western clothing type.

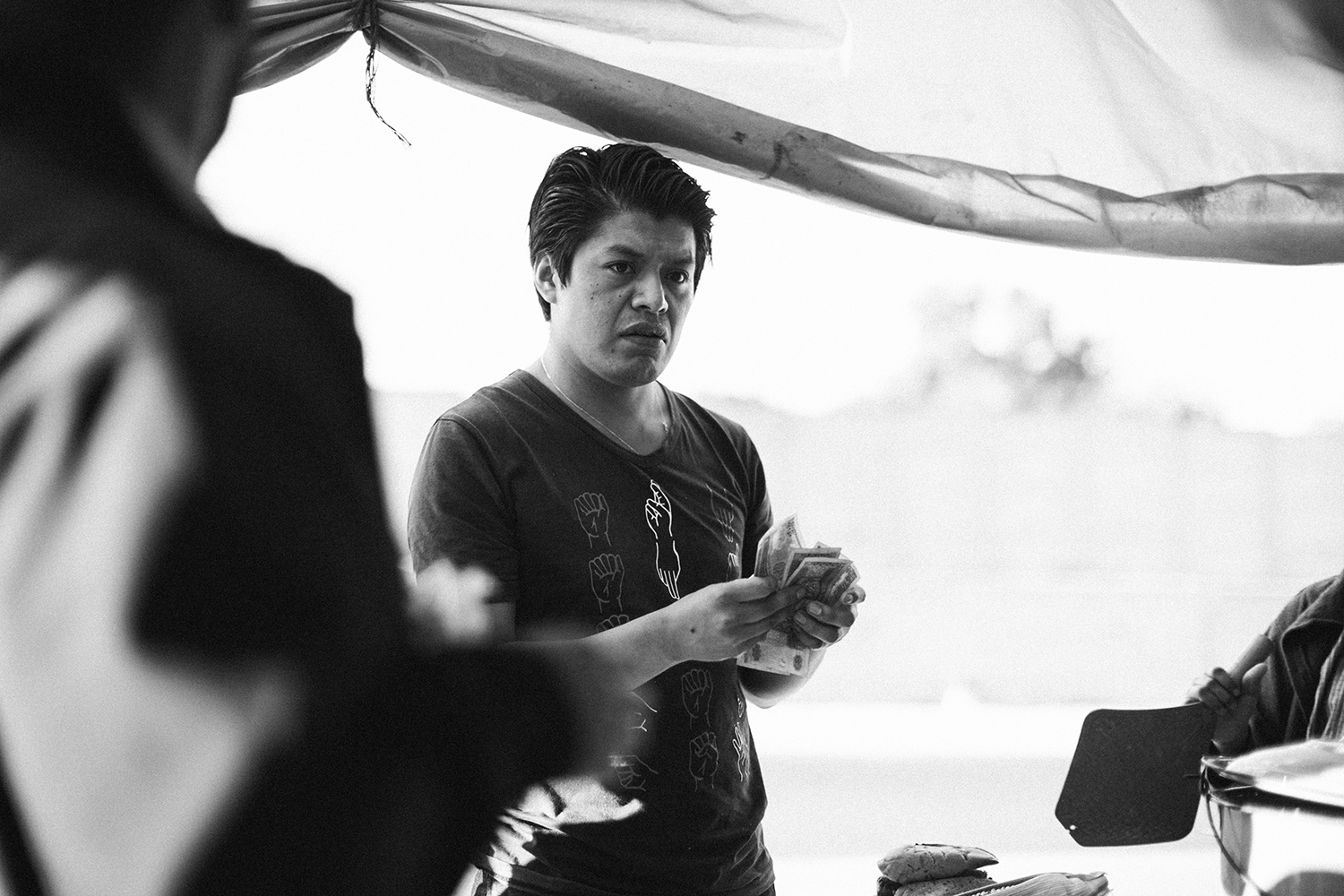

The people in my town, we’ve been there are of our time, and our parents, and our grandparents have been there all of their lives. We’re pretty much natives to the area. Its a good community feeling because you know everyone and everyone knows what everybody’s doing. It’s a small community. It’s different from the city though, because in the city you just don’t know anybody. In town is like everybody, you go to the street and walk, go downtown, go to the square. Usually every square has a fountain, so everybody hangs around the fountain, people buy and sell stuff.

There’s a culture of undermining the Maya, ever since the Spanish came here they made us seem, the Maya inferior to them. Generally speaking the Mayan person, or the indigenous person is less educated than the Latino Guatemalan, so having said that I want to clarify a couple of things. What happens is that the Mayan people feel as though they’re discriminated, we feel discriminated because the government doesn’t pay attention to us, like they do in bigger cities.

With this discrimination the Mayan people have tried to change their ways of living, their ways of speaking, to the extent that our languages are almost extinct. There’s a big population speaking, but if you find the Mayan person, with their Mayan outfit, they’ll probably speak to you in Spanish, because they are afraid that they are being double discriminated, because of their outfit and because of the language they speak. If they’re woman, that’s triple discrimination, right, because they’re also woman.

That’s why a lot of people just decide not to say that they speak Mayan. I don’t see it that way, because I want to let the people know that I value my culture, that I value the language that I was born with and that I was raised with and I’m not ashamed of that. For example, a simple example, in the Metro, the bus Metro, in Guatemala City you see a lot of people speaking in Spanish, I mean 100% Spanish, but their clothing says something different about them. Here’s what I saw the other day, the other day there was a man, I’m sorry a woman, with her Mayan typical clothing. She gets a phone call and she starts speaking in Spanish, broken Spanish. She prefers on broken Spanish than her Mayan language, which I think is wrong.

In my case, if my brother calls me, and if we speak on the phone, even if I’m in public places I just go like, “Kakchiquel Good afternoon, good morning. Kakchiquel What are you doing?” And, people just stare at me like, “What’s this stranger doing?” That’s how people look at me, but I don’t see it, I don’t get offended by it, because I do it because I’m identifying myself with the culture. I don’t get offended anymore. I just look at it in a different way.

It happens to everybody, for example, people from Africa they forget their language and they decide to go French or English. Why should we think that we are better than others? We’re different, yes of course we’re different color, different skin, but that makes us unique, right? It’s a very fine line, because if you want to change your ways of doing things you will. No one is going to stop you from doing that, but what keeps you on with your culture and your language is the benefit that you see in practicing your culture and your language. What benefit brings me to speak Mayan, or Kakchiquel? To me, personally, it brings me personal satisfaction. I’m an educated person and people show off when they say, “Well, I speak French. I speak Italian. I speak German,” then why can’t I show off that I know how to speak Kakchiquel? That’s the way I see it.

If I have to say something it’s just be proud of your own language. Think of it as, not inferior, but just as good as Spanish, English, German. Just as good. Just as fancy. It doesn’t matter if I deny my heritage, deny my language. I’m still Mayan, and that’s what keeps me moving and saying, “I’m going to be a different Mayan person.” I wish to see more Mayan lawyers, Mayan physicians wearing their outfits. Why not? Why do we have to accommodate ourselves to the western world when the western world can accommodate to our customs.

Someone from the US said, “Why don’t you worry about your own country and don’t compare yourself to us?” It really got into me and I thought about it really serious. To those who do not know anything outside the United States, or just anybody whom is used to stay at home, comfort zone, I have to say is, “Don’t be judgmental. Don’t be judgmental to the ways of living of other people, because while you enjoyed the benefits of a good government other countries are trying to develop a government.” That’s what’s happening in most of the third world countries.

When we talk about politics, when we talk about issues in regards of, “Why do we do mission trips? Why do you guys do this? Why don’t people take care of their own issues.” That’s being judgmental and I think that people really need to do the field work, right? In the US a doctor graduates with doctor practice, they already practiced, and that’s what we should do in life, everybody. Everybody should know the world, not by books but by going into the field and learning how it really works. Then you’ll have a better and critical way of thinking.

Don’t be judgmental. Go to other countries. If you really want to experience you have to see it first hand. Don’t take my word, come to Guatemala. •